January 30, 2018

This is one of a series of features, news articles and videos on the June 2017 conference “Is no local news bad news? Local journalism and its future” hosted by the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre. Watch the full conference panel below. To read more about the conference and local news, visit: localnews.journalism.ryerson.ca.

By GREGORY FURGALA

Staff reporter

Port Alberni is a typical British Columbia coastal town. Situated at the end of a deepwater inlet that meanders through the middle of Vancouver Island, it was colonized by MacMillan Bloedel and other logging companies before its temperate climate, surrounding mountains, and salmon drew in tourists who are colonizing it again. And like so many other small cities in B.C., it recently lost a newspaper.

Susan Quinn, the editor of the Alberni Valley News, wasn’t surprised when Glacier Media announced it was selling the Alberni Valley Times, her main competition, to Black Press. Aside from the rumours leading up to the deal, change of ownership at the Times was routine. Before Glacier bought it in 2011, the Times had been owned by Postmedia, CanWest, Hollinger, Southam, Sterling and an independent, non-chain owner. Quinn observed three of the sales from her perch at the News.

“It was just like when we heard CanWest was putting them up for sale, when Postmedia was putting them up for sale,” says Quinn. “It was almost anticlimactic.”

The sale was only part of a marquee 15-newspaper deal. In December 2014, Glacier Media agreed to sell 11 of its community newspapers on Vancouver Island—every newspaper except Victoria’s Times Colonist—to Black Press, its regional competitor. In a separate deal, Black Press sold its four Lower Mainland dailies to Glacier. After the 15-newspaper exchange, a wave of closures and layoffs played out, leaving Port Alberni and other two-newspaper towns with just one remaining publication, halving the diversity of local news, and halving the number of journalists reporting it, too. The 2017 Public Policy Forum report, the Shattered Mirror: News, Democracy and Trust in the Digital Age, makes it clear that Canadian newspapers are at a crisis point — nowhere is that more clear than B.C.

Quinn knows this but nevertheless, she remains optimistic about the future of local journalism.

…

She isn’t alone. A recent survey of 420 journalists and editors at small market newspapers in the United States found that most were upbeat about the future of local news and their jobs reporting it. Damian Radcliffe of the University of Oregon and Christopher Ali of the University of Virginia, who conducted the survey and interviews with 60 other industry professionals, presented their work at a 2017 Ryerson University conference on the future of local journalism. Respondents’ optimism, they concluded, was rooted in their connection to their communities, and knowledge that they’re often the only storytellers in town.

That finding—if it can be extrapolated to Canada —makes Heather Thomson an outlier. Thomson, the former editor the Alberni Valley Times, left a year before Black Press closed it. She says leaving wasn’t her choice, but rather the result of disagreements she had with the managing editor about the direction Glacier was taking the paper. She warns: “I’m pretty belligerent about them.”

“They were dictating how we would report news,” says Thomson. “We were being told who we could use as sources when it came to politicians. We were being told what stories we could work and who we could talk to. I didn’t agree with that, and I pushed against it for too long, and they got rid of me.”

In an email, a representative for Glacier Media said it does not dictate what its newspapers cover, or sources its journalists should talk to: “Editors are tasked with responsible and appropriate coverage of their respective communities and publishers are the final authority on what is published.”

Thomson, however, says Glacier’s overbearing management of the Times eroded its connection with the community and that quality news lost ground to the business of printing it. For Thomson, the local intimacy of reporting on the community she lived in, of being the local watchdog — the quality that hundreds of local American journalists credited for their continued albeit weathered enthusiasm — had slipped away. Thomson left the industry because of it, she says.

“In Port Alberni,” she says,” it used to matter what happened in the newspaper. It mattered to people. It mattered to the company that owned it, that they had a respected place in the community as the storyteller, and I think that’s what’s changing.

“It’s not about the story anymore. It’s becoming just about making money.”

…

The Local News Map, a crowd-sourced effort to document changes at local newspapers and broadcasters from the Local News Research Project, recorded the loss of 32 newspapers in British Columbia since 2008. Only Ontario has experienced more losses.

Marc Edge, a professor of journalism at both the University of Malta and Canada West University, says the B.C. closures were effectively orchestrated.

“It seems pretty obvious,” says Edge, “that they’ve been working together and carving up the industry between them.”

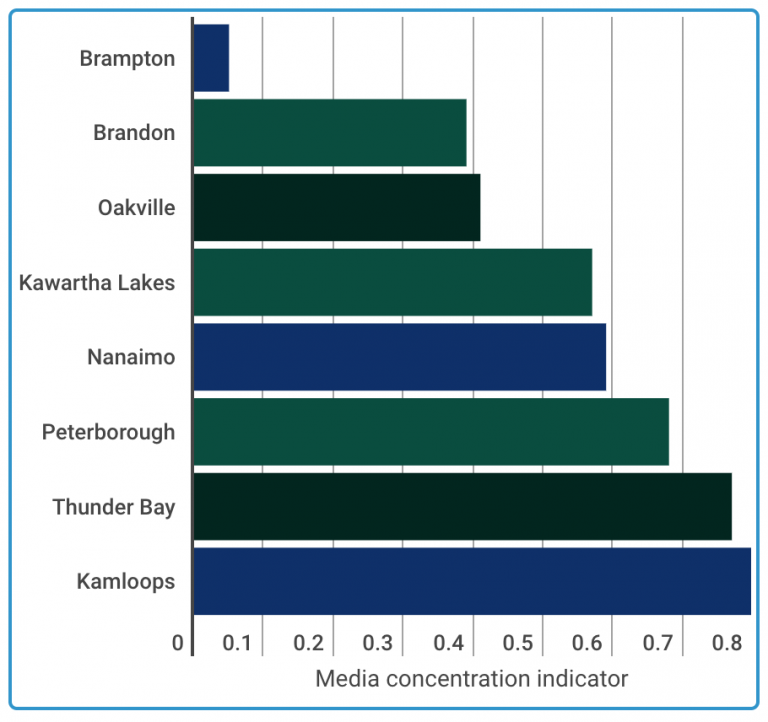

Local News Map data of news diversity in Canadian cities represent how much single outlets dominate coverage.

The reason isn’t particularly complex. Black and Glacier owned competing newspapers in several cities across B.C., like Port Alberni, and by buying up and shutting down the local competition, dwindling ad revenue could be directed to one newspaper, instead of shared by two. The Shattered Mirror report says ad revenue has dropped to $881 million in 2015 from $1.1 billion in 2006. While Edge notes that the traditional argument for newspaper concentration has been that it results in better-resourced survivors that put out better quality, better-designed publications, he doesn’t equate it with journalistic excellence.

“Graphic design and layout,” Edge says, “aren’t always indicators of good journalism, particularly the diversity of viewpoints.”

Maybe one newspaper had to close. While Quinn and Thomson have different outlooks on the future of community newspapers, both expressed doubt that Port Alberni could have supported two of them, especially as both operations were investing more time in producing content for their websites. And it’s worth noting that while the Times had been in print for decades, the News was only established in 2006. For far longer than not, Port Alberni has been a one-newspaper town.

Still though, the calculated dealings between Glacier and Black Press, and accelerated rate of closures in B.C. beg the question: If ad revenue continues to decline—and the Shattered Mirror report projects that it will—will another wave of deals be made out west? Is the worst over? And if it’s not, what’s there to be optimistic about?

…

Even before she left, Thomson says she bemoaned the increased demands placed on her and her newsroom. The prospect of being laid off loomed, she adds, from the day she started at the Times. Only weeks into the job, CanWest, which owned the paper at time, cut hundreds of positions across its all properties “to put more focus and resources on generating content and less on packaging,” a spokesperson told CBC at the time.

“I remember calling up the managing editor at the time and asking, ‘Do I still have a job to come to?’ Thomson says. “That’s the feeling I had the entire time I worked at the newspaper. I was always wondering when they were going to close the doors.”

These days Thomson works in public relations. She predicts the situation in the news business will get worse before it gets better but she hasn’t written off the news completely.

“I think at some point,” Thomson says, “someone will figure out a way it’ll make sense. I just don’t know what that will be.”

Since the Times closed, Quinn has added another reporter to the newsroom, and the News has gone from a weekly to a twice-weekly publication. Her newsroom uses a new content management system, which she says has helped streamline operations. Both are tangible investments. Technology, she says, is driving change, and her reporters are expected to produce stories differently than before. Two steps back, one step forward.